Pulled this out of the archive for new site

Primer

Within every customer, provider and transport network, there exists a host of applications that collect, disseminate and make decisions so that application services can communicate. These applications are also known as routing protocols and are at the core of how the Internet functions. The most common routing protocols used today include: Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)1, Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) 2 and IS-IS (Intermediate System - Intermediate System) 3

Often times the implementations of these protocols run in both virtual and physical platforms like Brocade, Cisco and Juniper routers exposing only a thin veneer to allow users to inspect, control and observe these applications.

What sets these applications apart from say your typical application service such as Nginx is they work in cooperation to maintain continuity of communications across both internally managed (non-autonomous) and externally managed (autonomous) entities. Given their distributed service, the lack of open interfaces and critical nature, we want to investigate building an application that can introspect their payload and possibly leverage this data to help enumerate network properties, diagnose problems or provide service assurance.

Observability

Observability is a property in control theory that allows us to infer the internal state of a system given knowledge of its inputs and outputs 4. To be fair, most routers do allow some visibility of internal state through operational and debug commands, but these are usually difficult to access and each implementation can render output in many different forms.

There is an effort being spearheaded to address the access to critical operational data through an effort called OpenConfig.

So what are we trying to accomplish? Obviously we do not want to build a fully functioning router that handles all of the various protocol features and algorithms but gather a subset of information that can be used for various goals.

Possible goals:

- Evaluate if networks in the output set are equal to the input set with the expected filtering policies applied.

- Measure the number of route-changes in the network correlated with administrative or operational events.

- Enumerate the entire network graph through careful inspection of protocol information.

- Can we determine if the number of neighbors in the system over time is accurate?

- Can we generate alerts on adjacency changes?

All of these can be assessed by deconstructing the protocol information into a useable form and inferring the behavior expected based on both internal and external constraints.

Design Evaluation

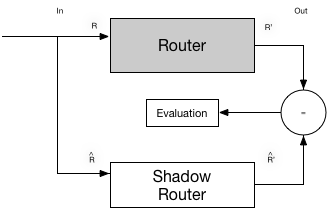

For goals 1-2 above we need a comparator to evaluate the output R’ and the estimated R^’ to calculate the difference of the two sets. The model for such a system is depicted below. The implementation splices off the inputs to the Router and copy them into a shadow router. The shadow router leverages a BPF HASH table located in kernel memory. The evaluator can then run on a scheduled interval and perform the necessary calculations.

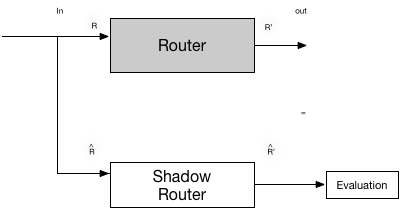

We find goals 3-5 to be simpler since we do not have to implement a comparator but simply collect information from the routing protocol to perform an evaluation on. The model for this is depicted below. We again splice off the input to the Router and copy them to the shadow router. We de-structure the protocol data into a set of fields and insert them into the BPF hash table. This is the fundamental design for an implementation we call RouteWatch

Introducing RouteWatch

First order of business was to establish requirements and understand the possible solutions.

- Leverage open source routing platforms like Quagga (now part of the Free Range Routing community)

- Record control-plane traffic from packet capture utilities such as TCPDUMP or Wireshark

- Run parsing commands on configuration and operational statistics of networking equipment

- Build something agnostic to the network device with enough flexibility to analyze any routing protocol.

We had dismissed the first option immediately since we knew the information we wanted was pushed deep within the data structures of the implementation and we didn’t want to fork off and maintain a custom version of the code. We also felt that we wanted to build something that didn’t rely on any one vendors implementation and would allow us to observe behavior between heterogeneous devices.

The second option was definitely doable, and would have been relatively simple given the wide use of libraries like libpcap. The problem was that we wanted to have the ability to design an event-driven model where we could create events to react to various rules and constraints we felt would provide the best facility for building a RouteWatch application without resorting to a post-processing ETL pipeline.

Writing parsers for command output is a complex task so we dismissed the third option as well. Dealing with all of the different vendor implementations is complex and fundamentally why building automation systems for network infrastructure is difficult. This issue is not necessarily solved by NetConf but that is a post for another day.

So ultimately we decided to go with building something ourselves that would give us the flexibility we needed and provide a stable foundation to build upon.

RouteWatch Requirements

- Be agnostic of any vendor hardware or VNF

- Be completely passive i.e. we don’t want to participate in the routing logic at all, or be in the critical path in any way

- Easily support thousands of adjacencies and tens of thousands of routing entries (scale to the maximum amount of locked memory available)

- Be flexible so that it can be tailored to any protocol, even non-routing protocols.

Technology

After some research we quickly gravitated towards the amazing work done by the Linux NetDev team on BPF. An in depth review of BPF was done by my collegue @im_ferris and can be read here: eBPF, part 1: Past, Present, and Future . You can also see a great talk by Thomas Graf from DockerCon discussing the use of BPF in Cilium.

In summary, BPF provides an in-kernel JIT-ed virtual machine that allows you to write code using a restricted version of C and run it within the kernel for maximal performance.

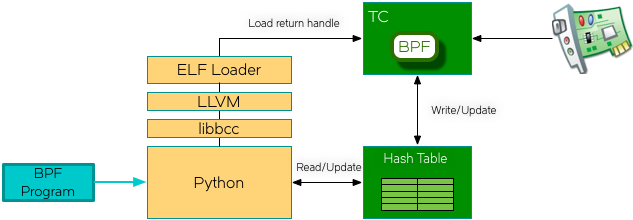

We decided to use the IOVisor BCC toolchain so we could leverage the Python native bindings to libbcc and allow python to handle the loading and interaction with the in-kernel hash table.

Lets look at the BPF Program

#include <uapi/linux/if_ether.h>

#include <uapi/linux/in.h>

#include <uapi/linux/pkt_cls.h>

#include <linux/string.h>

#include "is_is.h"

This is the main structure for our hash table. This structure models our adjacency table stored in-kernel and will hold all of the details of the IS-IS Hello frame we want to capture and store.

typedef struct adjacency

{

__u8 snpa[6];

__u8 circuit_type;

__u8 sysid[ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN];

__u16 hold_time;

__u16 pdu_len;

__u8 priority;

__u8 lanid[ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN + 1];

__u64 timestamp;

__u8 nlpid;

struct Neighbor neighbors[4];

struct Interface interfaces[4];

struct Area areas[4];

} adj_t;

This is the structure we will use as a key into our hash. It is comprised of the MAC source address + the IS-IS LANID

typedef struct table_key

{

__u8 src[6];

__u8 lanid[ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN + 1];

} table_key_t;

Here we use the BPF helper functions to initialize the HASH Map and provide a ring buffer to send messages to our Python application

BPF_HASH(adjacency, table_key_t, adj_t);

BPF_PERF_OUTPUT(skb_events);

Finally we have the function that is called each time a packet appears on the ingress interface.

This is fairly straightforward. We get a pointer to the raw payload of the packet in the skb data structure and then we test to see if we have accessed memory outside the bounds enforced by the verifier.

if (data + sizeof(*eth) + sizeof(*llc) + sizeof(*is_is) + sizeof(*iih) > data_end) return TC_ACT_SHOT;

We then test to see if we have an 802.3 frame and that it has the appropriate SSAP/DSAP identifier for IS-IS 0xFEFE.

Finally we add entries to the hash table and if they are new we signal this upstream by setting a sentinel value to 1. This is used to trigger an event in the user space application. We then take a note of the timestamp we got the packet update the table and send the packet up to user space for further processing.

Note: BPF programs are limited to 4096 instructions and we must ensure that looping terminates properly or the verifier will never load our program. There are various ways to accomplish this i.e. using tail calls but we chose to do this in user space for expediency.

int is_is_parse(struct __sk_buff *skb)

{

void *data = (void *)(long)skb->data;

void *data_end = (void *)(long)skb->data_end;

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

struct ethernet_llc *llc = data + sizeof(*eth);

struct is_is_header *is_is = data + sizeof(*eth) + sizeof(*llc);

struct is_is_hello_header *iih = data + sizeof(*eth) + sizeof(*llc) + sizeof(*is_is);

/* single length check */

if (data + sizeof(*eth) + sizeof(*llc) + sizeof(*is_is) + sizeof(*iih) > data_end)

return TC_ACT_SHOT;

if (eth->h_proto <= htons(ETH_DATA_LEN) && llc->sap == ISISSAP && is_is->pdu_type == PDU_HELLO)

{

__u32 magic;

__u64 stest;

table_key_t tk;

adj_t zleaf = {0};

memcpy(tk.src, eth->h_source, 6);

memcpy(tk.lanid, iih->lanid, ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN + 1);

adj_t *a = adjacency.lookup_or_init(&tk, &zleaf);

if (a)

{

stest = *((__u64 *)a->snpa);

(stest == 0) ? (magic = 1) : (magic = 0);

memcpy(a->snpa, eth->h_source, 6);

a->circuit_type = iih->circuit_type;

memcpy(a->sysid, iih->sysid, ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN);

a->hold_time = ntohs(iih->hold_time);

a->pdu_len = ntohs(iih->pdu_len);

a->priority = iih->priority;

memcpy(a->lanid, iih->lanid, ISIS_SYS_ID_LEN + 1);

a->timestamp = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

skb_events.perf_submit_skb(skb, skb->len, &magic, sizeof(magic));

return TC_ACT_OK;

// }

}

}

else

return TC_ACT_OK;

return TC_ACT_OK;

}

Now we are going to step into the userspace program.

The IOVisor toolchain allows clients to leverage Python, Lua or C++. Here we will demonstrate a python application.

If you remember in our architecture diagram above we are loading our program into the TC subsystem using the bpf system call. Accessing netdev/switchdev services is done through the Netlink protocol. The Pyroute2 library gives us access to this as demonstrated below.

def tc(self):

def isInstalled():

q = self.ipr.get_qdiscs(index=self.interface_index)

if len(q) > 1:

(attr, val) = q[1]['attrs'][0]

if 'clsact' in val:

return True

else:

return False

else:

return False

installFlag = bool(isInstalled())

if not installFlag:

assert isInstalled is not True

self.ipr.tc('add', 'clsact', index=self.interface_index)

rn = randint(1, 100)

self.ipr.tc("add-filter", "bpf", index=self.interface_index, handle=":{}".format(rn),

fd=self.parser.fd, name=self.parser.name, parent="ffff:fff2", direct_action=True)

self.adjacency_table = self.b.get_table("adjacency", table_key, adjacency)

The skb_events function provides the main loop of the program. We issue a kprobe_poll and block for 1000ms after which we run the cache_invalidation algorithm.

The open_perf_buffer method call takes a callback function to execute if there is anything in the perf ring-buffer. Every time we have a new frame to parse we fire off the parse_tlv method to extract the TLV data of the payload.

def skb_events(self):

try:

self.b["skb_events"].open_perf_buffer(self.parse_tlv)

except KeyError, e:

print("Key doesn't exist: error {}".format(str(e)))

except:

raise

while True:

self.b.kprobe_poll(1000)

self.cache_invalidate()

Notice we are using the ctypes library to coerce our raw data into Python types.

def parse_tlv(self, cpu, data, size):

tlv_map = {}

class SkbEvent(ct.Structure):

_fields_ = [("magic", ct.c_uint32),

("raw", ct.c_ubyte * (size - ct.sizeof(ct.c_uint32)))]

skb_event = ct.cast(data, ct.POINTER(SkbEvent)).contents

magic = skb_event.magic

raw = bytearray(skb_event.raw)

if self.debug:

print("Adjacency event: ", magic)

src = binascii.hexlify(raw[6:12])

lanid = binascii.hexlify(raw[37:44])

if self.debug:

print("LANID Value: ", int(lanid))

# update user table.

tlv = raw[44:]

tlv_length = len(tlv)

assert tlv_length > 0

key = self.adjacency_table.Key(hexstring_ubyte(src), hexstring_ubyte(lanid))

if self.debug:

print("Key Value: ", ubyte_string(key))

d1 = self.adjacency_table[key]

d2 = parse_handler(tlv_length, tlv, tlv_map)

assert d1 is not None

assert d2 is not None

# Test for new adjacency and alert

sysid = ubyte_string(d1.sysid)

lspid = "{}0000".format(sysid)

if int(lanid) is not 0:

if(magic == 1):

snmpTrap(targets, 1, lspid, "up")

for k in d2.iterkeys():

self.update_hash(key, k, d2[k])

Recursive parse handler. Calls parse_fns for each type found in TLV payload

def parse_handler(length, tlv, coll):

(type, l) = struct.unpack('!BB', tlv[:2])

tlv_skip = tlv[2:] # skip type value

if type in parse_fns:

parse_fns[type](l, tlv_skip, coll)

next_tlv = tlv[l + 2:] # Move pointer and call again

try:

parse_handler(len(next_tlv), next_tlv, coll)

except:

"Print issue parsing TLV"

return coll

The cache_invalidate function is the only algorithm we need in this application. It simply evaluates the hold_time to see if it has reached 0. This would mean we have not seen another IS-IS Hello packet within the hold-time interval and we remove the entry from the table and issue an snmpTrap. Of course this could be any event you wanted to generate to alert your operations that we have a failure of one of our peers. This could indicate a loss somewhere in the transport network or failure of the route instance itself.

def cache_invalidate(self):

for k, v in self.adjacency_table.items():

table = self.adjacency_table

leaf = table[k]

sysid = the(leaf.sysid)

lspid = "{}0000".format(sysid)

if (leaf.hold_time == 0):

snmpTrap(targets, 1, lspid, "down")

table.__delitem__(k)

else:

leaf.hold_time -= 1

table.__setitem__(k, leaf)

if self.debug:

if self.adjacency_table.values():

dump_table(self.adjacency_table)

Here is a demonstration of the application that is running between 3 IS-IS Quagga Instances. You will notice how the hold_time counts down and then restarts back at 50 seconds when it receives a new IIH packet. You will also notice that the table includes all areas so this is an aggregate that usually is isolated within seperate IS-IS instances.

Summary

BPF is an amazing technology for dynamically inserting code into the kernel in a safe and controlled way to create new applications. We have demonstrated how you can leverage BPF to capture routing protocol data and leverage the BPF hash tables to store application state that can be used to simulate a real router adjacency table. This could be expanded to support various use-cases in performing control plane analytics and OAM services.